Srinivas Krishna is a member of the VRARA Storytelling Committee and the Founder and CEO of the pioneering mobile AR studio AWE Company (2012) and the mobile AR platform Geogram (2017). He joins VRARA's Storyteller Davar Ardalan to talk about his foundational work in AR technologies, some of the most remarkable AR experiences of the past decade. His work as a digital media innovator has been applauded by Canada’s national newspaper, The Globe and Mail, as “utterly breathtaking… genius.”

Prior to his work in augmented reality, Srinivas produced and directed feature films that have premiered at Toronto, Sundance and Cannes, and have been distributed worldwide. He launched his career in 1991 with the international hit Masala, which was voted by the British Film Institute among the Top Ten South Asian Diaspora Films of the 20th Century and is a classic of world cinema.

1) You are a pioneer in VR & AR storytelling and came to this space as a filmmaker. For those who still haven’t experienced immersive media - what is intriguing about it and why should they try it?

Immersive media is quite different from the movies. I started experimenting in this space after making films for twenty years. In 2010, my studio was commissioned to produce 10 films on athletes competing in the Vancouver Winter Olympics. One of the requirements was to geo-locate clips of the athletes for playback on users' phones at various competition venues. This sounds relatively easy to do today. But, in 2010, two years after the introduction of the smartphone, it was a challenge.

This project got me thinking about the larger implications of distributing and delivering contextually-aware, narrative content for smartphone users. Around the same time, I saw my three year-old son walking around with my newly acquired iPad. He was playing with the pre-loaded game demo from Unreal. Watching him inspired a vision. What if you could inhabit these 3D worlds? What if we could marry them to the real world and walk around inside them and interact with their characters and events? It was an epiphany.

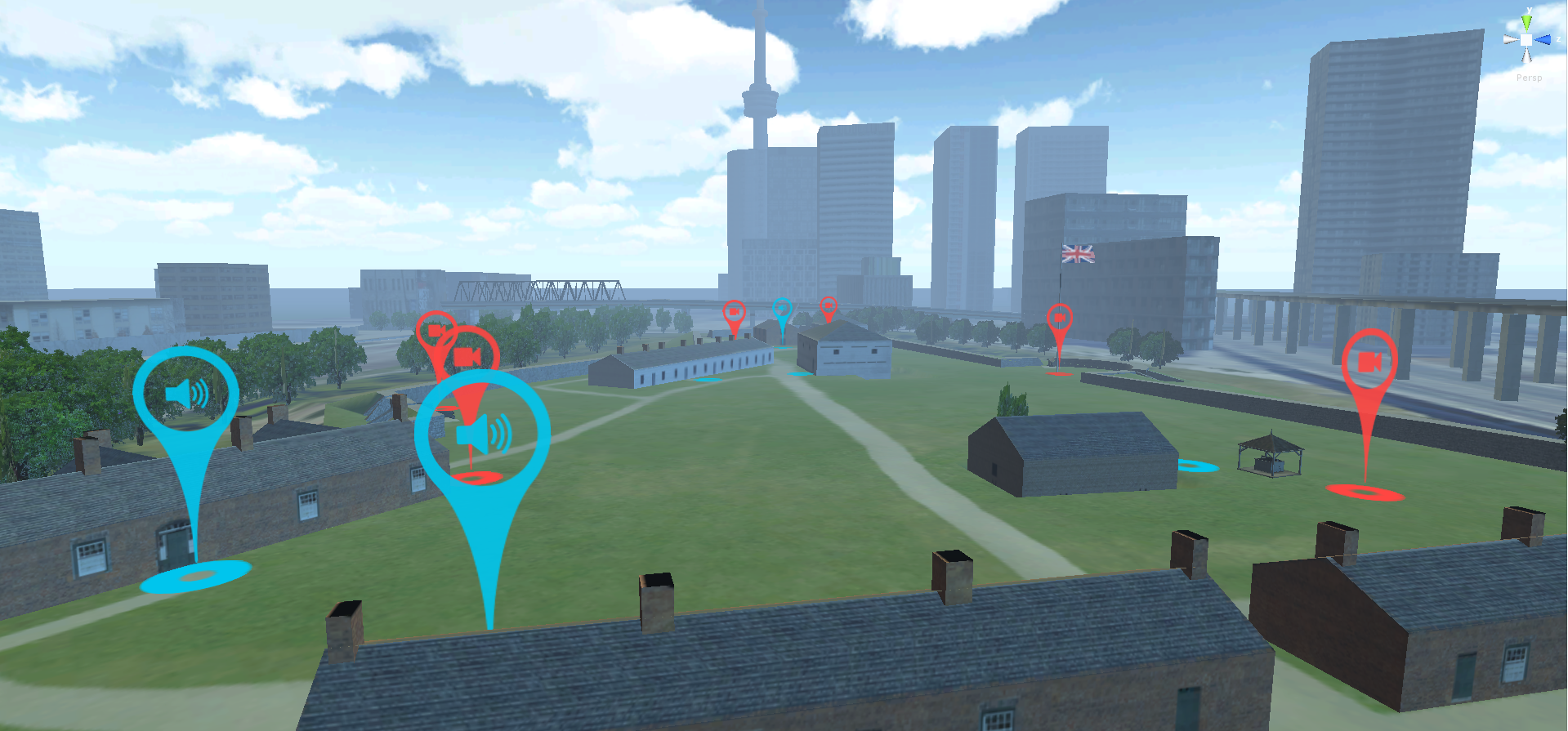

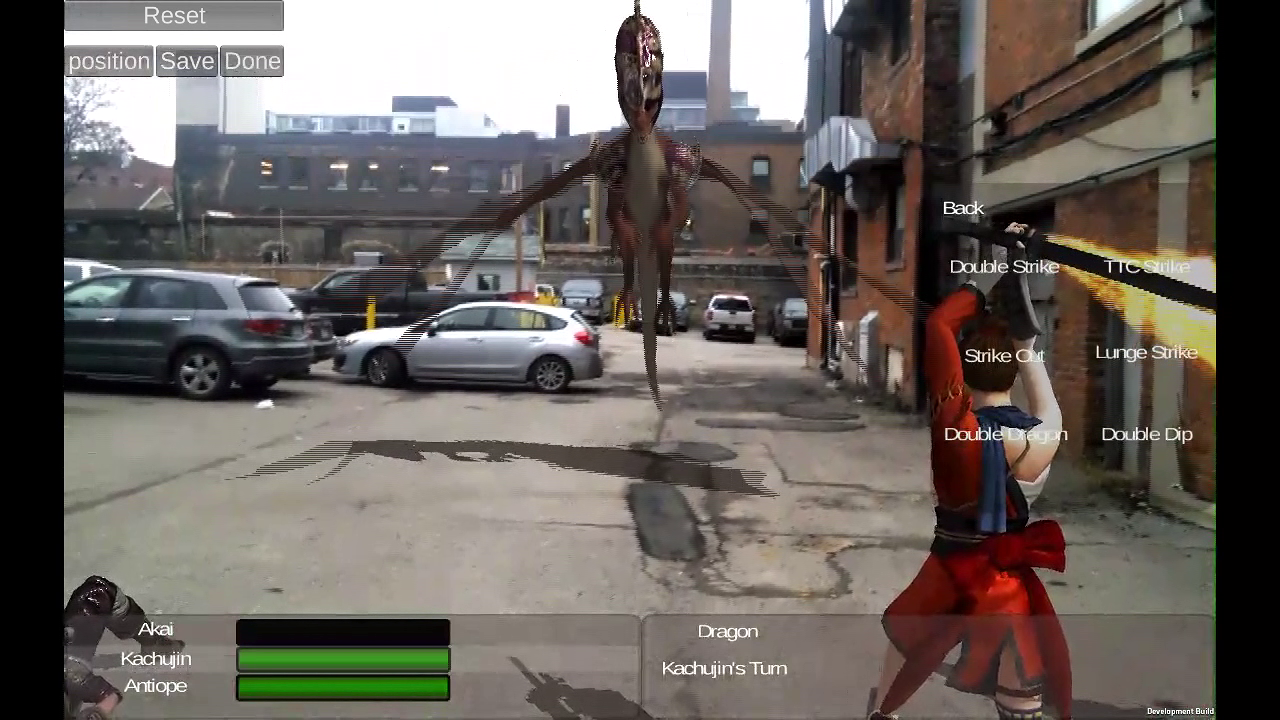

I spent a year looking for people who could build the tech to support this kind of experience. I finally found a team of scientists at Ryerson University's Multimedia Lab who didn't think I was crazy. We started a collaboration and, by 2012, I was developing and staging my first multi-user, room scale experience. It was a mixed reality historical drama for five untethered iPad users interacting with a cast of a dozen virtual humans, set in the oldest building in Toronto, a defensive bunker in old Fort York called the Blockhouse.

You can see highlights in this video:

The Blockhouse was the first time anyone had experienced anything like this -- an audience in a room individually and collectively interacting with virtual humans who know you're there, who talk to you, even take a run at you. We ran hundreds of users through the experience and did countless focus groups and user interviews. The whole project became, in a sense, a social experiment -- about human beings and how they relate to new technologies and experiences, why they might resist, and how to build trust, drive adoption and create pleasure. I learned so much

What I discovered was a fundamentally different medium. Immersive media - and let me be clear that I'm talking about unthered mobile experiences - is more like theatre than film. It places you in a location and runs in real time, much like a show on a stage. But it's also different from the theatre - because it puts you in the middle of the show and lets you interact with it. There can be sudden changes in scale, and changes in the location and time period of the world you are inhabiting, done digitally in a way that's not possible on a real stage.

Moreover, you, the audience, require a device to access the show; in a sense, you become the cameraman of your own experience, holding a magic window into this other world. So where you look and how you navigate this world, as you walk around inside it and respond to it, will determine the kind of experience you'll have. It is a spatialized experience, unlike the 2D onscreen interfaces we are accustomed to, so there's a learning curve to it. I have seen users do nothing more than look through their devices at their feet for an entire 15 minute experience, despite all the noise and action happening around them, while others dance around the room and have full on conversations with the virtual characters.

Therefore, as someone who creates immersive experiences, it's important to realise that you are not only staging the performance of the virtual characters and organizing the behavior of their virtual world, you are also choreographing the response, movements and gaze of the user in relation to them. That's the art of it.

Now imagine doing that for multiple users inhabiting the same show and interacting with the same virtual characters, all in a real world location, all at the same time. It can be mind-boggling to plan and execute. But, when it's done well, the experience can be absolutely mind-blowing, utterly unpredictable and just plain crazy fun.

2) What was the first project you monetized when you knew you could make a living doing this work?

After our demo at the Blockhouse, I got a slew of mobile AR VR projects in 2014 to 2017. These included a location-based AR adaptation of a mobile video game, an AR component to a web cartoon, a large scale visitor attraction for the Fort York National Historic site in downtown Toronto. My studio changed completely from doing film and TV to AR VR. We hired engineers and scientists. We developed new technologies and work flows. We produced experiences that were the first of their kind. We were inventing a new medium. And, incredibly, we made a living doing it. This was a hugely exciting time and it remains so to this day.

3) Tell us more about your pioneering mobile AR project at Fort York in Toronto and the patented tech you built in the process.

The prototype I built in collaboration with the scientists at the Blockhouse in 2012-13 was, as far as we knew, the first demonstration of multi-user, interactive, collaborative mobile mixed reality. We tracked the exact positions and poses of five iPad users as they moved around the shared space by using the devices' on board sensors and a slam algorithm. We communicated the users' location data to a server. Our mixed reality engine would render the virtual content in the users' video feeds, in real-time, according to each user's unique position and pose. We filed a patent application for our system and method in 2013 and were finally granted the patent by the USPTO in April 2018. Throughout these years, we've been building out our tech through our many projects.

The most complicated and challenging of these projects was a visitor attraction at Fort York National Historic Site in Toronto. It required us to scale our prototype from 5 iPad users in a single room to a hundred thousand plus annual visitors at a nine acre Site; it meant tracking their location as they explored the grounds of the Fort and delivering, through smartphones, immersive recreations of historic events that took place right where they are standing.

We started in 2014 by improving our tech stack so we could track a lot more users' positions and poses across the Site, and optimizing our slam algorithm so that we could deliver markerless AR on the consumer devices available back then. Because the client wanted historic recreations, we realised that conventional mixed reality wouldn't work; we'd end up placing virtual characters from the 18th century in a location surrounded by 20th century condo towers, and that would be jarring, comical, and weird. Instead, we built complete 360 degree worlds that would effectively take the visitor out of the present and immerse them convincingly in the past. In the end, we built eight of these worlds, from a depiction of the Site as it appeared before European settlement, to a battle scene from the War of 1813, to the construction of an elevated highway in the 1950's that's still there today.

Here's how we did it -- we scanned the entire Site and created a model that we used to situate, scale and sculpt these virtual worlds into the topography of the Site. We did low cost 3D scans of real people on iPads to create our characters, did motion capture using Sony Playstation cameras and a great software called iPiSoft, and built a rich binaural soundtrack to lead visitors through the two hour experience from start to finish.

Amazingly, by the spring of 2015, we were ready for user testing -- and that began a whole new social experiment in spatialized UI and a whole new set of lessons to learn. Suffice to say, by the Fall of 2015 we had achieved at Net Promoter Score of 9.3. The project was launched as the TimeWarp VR Experience at Fort York and we started getting our first paying customers. At the time, we were among the few companies, if not the only one, to have a consumer mobile AR experience of that scale, complete with our own tech stack and UI, in the market.

I think it's reasonable to say that the TimeWarp VR Experience at Fort York is a milestone in the early history of mobile AR, something that years later people will look at and say, "Here's the crazy shit they used to do before Google, Apple and Facebook made it all so easy!" I gave a rather entertaining fifteen minute talk about our roller coaster journey from prototype to paying customers at the AR in Action Summit at MIT in 2016. (You can watch it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e7kThp0mFhA). Now, two years later, we are building version 2, incorporating AR Kit and AR Core. And, yes, these tools do make it easier.

4) Are there regions of the world where consumers are more actively engaged in buying VR and AR experiences?

When it comes to consumer AR VR, I believe all roads lead to China. I read an article recently in VR Scout (https://vrscout.com/news/rise-consumer-ar-china/#) that quotes a survey indicating that 95% of Chinese consumers have used AR or VR technology in the past three months compared to only 24% of U.S. consumers. Another survey of 2,000 Chinese Internet users revealed that 78% actively seek out AR products. The reasons for such strong consumer adoption rates are quite obvious. China is a mobile first country with cheap data plans and a massive and growing online user base, most of them accessing the web on mobile. I believe for these reasons Africa, India, and much of South East Asia will follow.

5) Any advice for current VR and AR students on where the industry is headed 2-3 years from now?

With the incumbents -- Google, Apple Facebook and the rest -- having entered the space so aggressively, we can safely say that the era of the spatialized web has begun. Over the next 2 to 3 years, we'll start seeing early consumer adoption of smart glasses while, at the same time, we'll witness AR VR integrating with IOT and AI to make the physical world increasingly intelligent as it goes online. This has enormous implications.

For VR and AR students today, this means we are moving up the stack from core tech and middleware to user data, design and content layers. No longer is it really about the tech, it's about how we will use this tech to create value. What type of content and what kind of experiences will make life better? What kind of user interfaces will help us navigate and interact with an intelligent, spatialized web? How will the blockchain and decentralized data architecture enable greater individual liberty in terms of the stories and information we share in an online space that communicates intelligently with our physical world? This is where I would advise VR and AR students to look for opportunities.

At the same time, as an industry, it's important that we learn from the past and avoid making the same mistakes, those countless choices, big and small, that have led us from an open internet to monopolies and mass surveillence. But the world is about change, all over again, and we have a chance to make a real difference. That's what makes this moment so exciting.